In 1879 a 25-year old Belgian named Alfred Blondel traveled around the world to complement his education in science and engineering. His travels took him through Northern China and Mongolia, and when his great granddaughter, Martine Bouquelle of Brussels came across his diary, she contacted Christian Goens because she found three weeks worth of annotations on his travels with Paul Splingaerd, a major subject of Christian’s website.

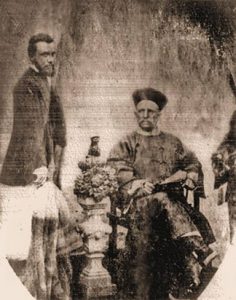

Figure 1. Alfred Blondel with Paul Splingaerd, Kalgan, 1879

Mme Bouquelle painstakingly transcribed her ancestor’s notes and kindly shared them with Belgian Christian Goens and me. Her ancestor’s descriptions offer a first-hand glimpse into the time and places that Paul lived in, and valuable insights into the personality of the man who would later be known as “The Belgian Mandarin.”

We thank Mme Bouquelle for her permission to translate and share excerpts from Mr. Blondel’s diary, and the pictures of her ancestor with Paul. These cannot be considered any less than a priceless contribution to the story of Paul Splingaerd.

In this English translation of selected passages, I use the modern pinyin spelling of Chinese name places for clarity whenever possible. For the French names, please refer to the French version at http://goens.splingaerd.net/multima-pourbaix/Mandarijn/Documents/Blondel1/extracts.htm. Christian has provided the illustrations for this translation. — AM

April 30

Towards 2 in the afternoon we arrived at Tianjin, having completed in 3 days the 1,219 km. that separate it from Shanghai. [Blondel arrived in Shanghai from Japan on April 24, 1879.]

We disembark, and my companions and I head for the Lazaristt[1] mission where we are warmly welcomed by Frs. Favier, Wynhoven and Salette.

Since the horrible massacre of Christians that took place in Tianjin in June of 1870, in which the French consul and numerous nuns and priests perished, the church and the residence of the Lazarists have been inside the concession.

Concession is the name given to the district inhabited by Europeans in the treaty ports. This district is always outside the city walls.

Towards evening we are visited by Mr. Splingaerd, a Belgian businessman established in Mongolia. Mr. S. is a Brussels native, seems to between 35 and 38. He is short, neither fat nor thin, of a gay spirit, and full of energy. He has a very open character, and struck me instantly as being a most likeable fellow.

Arriving in China about fifteen years ago, he spent some time as an interpreter at the German Legation in Beijing. It was in this capacity he traveled throughout China with German geologist, Baron Von Richtoven [sic.] to whom he was able to render great services thanks to his knowledge of languages. He speaks Flemish, French; German, Chinese, Japanese and Mongolian! … [in later years he would also speak Russian and Turkish from working in Central Asia.]

He has been wearing Chinese garb for a long time, and I gather from his long queue that our [European] hair is adaptable to the style of the children of the Middle Kingdom.

Mr. S is married to a Chinese woman from a noble family, and lives in the city of Huhehote, not far from the Huang He, the Yellow River, where he trades in camelhair.

With a recently acquired German associate, he has established a freight depot in Kalgan, located at the Great Wall of China.

Our compatriot has just arrived from Ourga [Ulaanbaatar today], on the frontier between Mongolia and Siberia.

He gives me interesting details on the latter.

May 1

Mr. Splingaerd would like to be our guide to the city of Tanjin.

Frs. De Boeck, Kissel and myself bravely mounted miserable donkeys and the four of us make our solemn entrance into the city of Pe-Chi-Li (Zhili).[2]

Tientsin is a city of 600,000 inhabitants located 60 km from the sea on flat and marshy terrain at the confluence of the Grand Canal with the Pei Ho.

This is the famous Grand Canal that connects the Pei-Ho (Bai He is now called the Hai River) with the Yellow River and the Yangtse Jiang (Yangzi or Chang Jiang today) to the Blue River.

A large crenellated wall with stinking ditches is what first strikes the visitor.

This city is huge and is made still larger by a suburb to the north.

…

Here the streets are wider and the shops relatively fine.

In China, merchants of the same merchandise occupy the same streets.

We find the Avenue of Eternal Prosperity where the clothing stores are located.

A beautiful silk dress costs 200 to 300 francs.

Then we go to the fur shops street.

Tientsin is very famous for its furs stores.

Thanks to Mr Splingaerd who has a thorough knowledge of Chinese, we make some acquisitions.

On entering a shop, the merchant “chin-chins”[3] us.

The term chin-chin refers to the Chinese greeting. In this kind of greeting, they clasp hands is up to the chest, then shakes his head on the left side with the words chin-chin.

This is something very comical.

Leaving the fur shops, we remount our donkeys and return to the mission.

…

At about one o’clock we are back at the mission.

It was decided that tomorrow we leave for Beijing, not by dirt road but by getting back in the Pei-Ho.

We are fortunate to have the company of Mr. Splingaerd who is returning to Mongolia.

Towards evening, the Belgian consul sends me my passport to Beijing.

It is a beautiful masterpiece of Chinese calligraphy.

I have to note that our names cannot be translated into Chinese or there are no characters to write them with.

The Tianjin mandarin has baptized me with the name of “Pou-Lon-Tchou.”

What connection between that name and Blondel? I have never figured it out.

May 2

At 9 o’clock in the morning we say goodbye to the excellent Wynhoven and the four of us embark on the 3 boats that must bring us to Tung Chao.

The two missionaries occupy the same boat, Splingaerd has one and I occupy the third.

These boats are fairly flat, 5 meters long, 1.5 meters wide

A light roof supported by movable panels covers 2 / 3 the length.

Each boat is equipped with a sail and three crewmen.

May 5

The next day, the excellent Mr Splingaerd wants to show me around the city [Beijing]. He first brings me to the top of the wall to capture with one glance the characteristic roofs of Beijing.

This immense city has two distinct parts, the Chinese city and the Tartar City. Both are rectangular and contiguous to each other and each surrounded by a high wall so that the south wall of the Tartar district forms the north wall of the Chinese section.

The extent of these 2 cities is about 40 sq. km.

It is very difficult to assign a number to the population of Beijing, since the Chinese government has never taken a census. Some speak of 2 million, others say 1 million and even 900,000 residents. It is likely that the exact number does not exceed 600,000 souls.

When you cast a glance at this city, which strikes your eye first is all the different colored roofs. Many houses are covered with colored glazed tiles. There are sky-blue roofs, yellow, orange and soft green. This was something very strange and in bright sunshine, it is certainly very lovely.

The palace of the Emperor occupies a vast rectangle in the center of the Tartar district. There all the roofs are yellow, the proper color for all imperial buildings.

Here and there, large gardens, groves of trees and parks stand out in sharp contrast to all these monotonous buildings and streets, which intersect at right angles.

It is from the top of the city wall that you can enjoy the best view of Beijing. Here you are on top of the city and the eye follows perfectly all sides of the parallelogram formed by the 2 cities.

The wall is really enormous, it is 33 km long, it rests on stone foundations and consists of two walls slightly inclined towards each other, the space between them is filled with earth.

The wall has a height of 13 m and a width of 10 m at the summit.

By walking along the wall that Splingaerd and I arrive at the observatory established on the same wall. The observatory was built in 1674 by order of the Emperor Kangxi based on plans drawn by Father Verbiest, a Jesuit born in Pittem, Belgium near Kortrijk.

…

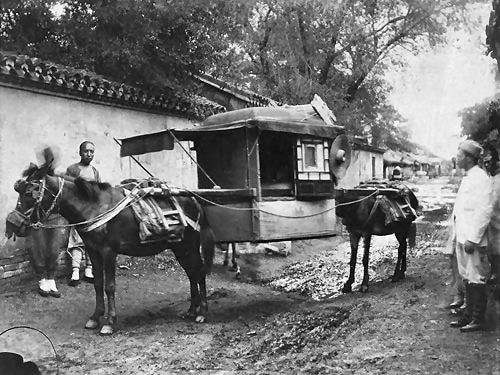

Today Splingaerd and I are to have dinner at Beitang, Monseigneur de Laplace sent us an invitation last night. To get from the hotel to the Beitang mission, we traverse the whole city in a cab.

The Beijing cab certainly merits a description: imagine a vehicle without springs, no seat, covered with blue cloth and pulled by a mule. It’s more like a wagon than anything else. It seems that this instrument of torture was around since the time of Confucius,.

The Beijing cab certainly merits a description: imagine a vehicle without springs, no seat, covered with blue cloth and pulled by a mule. It’s more like a wagon than anything else. It seems that this instrument of torture was around since the time of Confucius,.

…

Towards noon, we arrive at the Beitang, which includes the diocesan offices, the Cathedral and the Catholic seminary in Beijing.

Splingaerd and I are received courteously by Monsignor Delaplace, Fr Favier, his vicar general, and the other missionaries.

All these gentlemen are members of the Lazarist congregation of Paris who has all the Catholic missions of Zhili, except a small part which belongs to the Jesuits.

May 8

Today, Frs. De Boeck and Kissel leave for Mongolia.

Splingaerd has business that keeps him in Beijing, but proposes to accompany me in a few days to the Great Wall.

Prince Alashan-Wan, brother of the king of Mongolia, is coming to visit my companion.

This high dignitary greets us with a gracious “chin chin”.

He is accompanied by a secretary and a large mounted escort.

Although I cannot understand a word of conversation, I think that Prince does not appear to be hostile to the Europeans and seems like a pleasant fellow.

Some of the soldiers escorting him, who stood first at the door finally enter the room and at the end of the visit, some of them are sitting on the sofas.

There are between senior Chinese officials and their subordinates a curious mixture of haughtiness and camaraderie.

After his visitor’s departure, S. informs me that the prince has another brother who is a living Buddha. We know that Buddhists give this name to a few characters elevated to divinity.

The King of Mongolia has to marry a daughter of the Emperor of China, and the present king is married to a daughter of Prince Kang.

…

In the evening Splingaerd announces that his business is completed and we leave tomorrow for Mongolia.

May 9

At 5am, general commotion in the hotel.

We will travel by palanquin to the Great Wall.

Pictured are coolie-drawn sedan chair in the foreground, and rickshaw on the left

Our caravan consisted of my excellent companion, me, a cook, my interpreter Chang and 4 mule drivers. We have 4 baggage mules and 4 for the palanquins.

The palanquin is a sort of large sedan chair with no seat, where you lie as in a litter. It is supported at the front and rear by a pair of shafts, 2 mules carry this strange device.

…..

At this time of year the wheat fields are green, and the rice paddies resemble wetlands.

Many children play on the road by rolling in the dust.

Here and there you will see us push the cry of “yan-qué-dze” which means “devil of a stranger.”

The curiosity of the population is beginning to annoy me, when we pass through a village, it is always through a crowd of curious people lined up to look at me. I do not say “we” because Splingaerd, dressed in Chinese garb, attracts much less attention.

…..

All the inns in China are built on the same plan: Imagine a rectangular courtyard, whose sides are formed by the guest house and two others in shelters covered with straw used as a stable.

The residential building is low, without basements or attics. The rooms are placed next to each other, with all their doors overlooking the courtyard. Their frontage, windows and doors are of wood covered with paper.

The interior of the rooms could not be simpler, the soil is of beaten earth, the ceiling is also the roof, and the walls were whitewashed 10 years ago. A long Chinese kang occupies an entire side of the room.

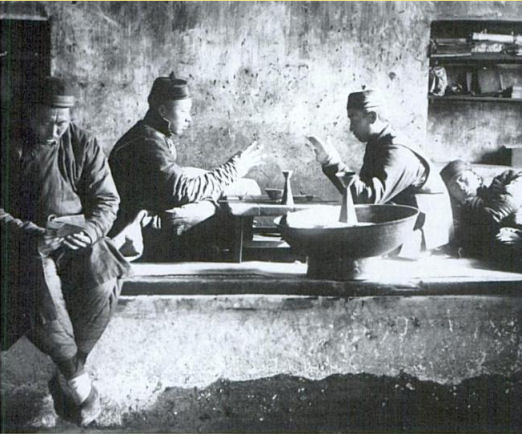

A kang, where one sits plays and sleeps

The kang is a flat area of masonry about 1m above the ground.

In this mass of masonry are tin pipes leading from a hearth on one side to a chimney on the other.

By burning some firewood, the kang is quickly heated, and on this surface the traveler lays out his wolf skin, envelops himself in a blanket, and abandons himself to sleep.

It is surrounded by at least 30 people, that Splingaerd and I eat our dinner. The whole village would come and watch, it’s so funny, so strange to see Europeans eat, it’s like going to wild beasts eat a meal in a menagerie! ….

Let us not criticize Chinese curiosity too much. The other day Montagne de la Cour in Brussels, I saw a poor fellow followed around by 50 people.

My companion, who knows the Chinese language as his own is very gay and amusing in his witty repartees.

A little hunchback, believing that only our hands and our faces were white, asked if we had a yellow body. “Yes,” replied Splingaerd, “we are two colors. It’s like you, except for your face and your hands I know you’re black ”

…..

May 12

Wanting to try Chinese cuisine, S. and I turn our lunch into our “tiffin”, name the Chinese gave the second lunch, by having a soup with long strands of oat dough, like our vermicelli. This soup is followed by a porridge of millet grains, and other de-husked grains. This food makes me involuntarily think of the relationship between canaries and Chinese …. Finally some grilled meat of some unidentified animal advantageously complements the two previous boiled dishes. For bread, we eat little cubes of compact white dough covered with a smooth yellow crust.

May 19 [or possibly 14th?]*

But now our palanquins have arrived close to the coalmine I mentioned yesterday.

To our right is a series of shale hills and it seems that this is the coalfield in question.

We step out in front of the door of a shabby hut located at the entrance of the mine.

A long discussion takes place here between S. and the deputy chief who does not let us enter.

I ask him questions about the richness, depth, direction, speed of the mine and veins operated on the depth underground, ventilation, extraction method employed, etc. …

To all these questions, my Chinese [translator Chang] is content to look at me stupidly nodding his head, or answered in a beautiful stupidity.

Seeing that there is nothing to be learned, S. manages to convince the fellow to let us enter the mine. For a guide, we are provided with a 15-year-old boy with downcast eyes and a beaming face. It goes without saying that it would be impossible for the latter, even with the best intentions, to answer any questions.

We roll up our pants, I don a woolen cap and accept a bad little cast iron lamp with a wick submerged in oil, which has to serve us as illumination.

The gate of the mine being open, just imagine a long square tunnel on an inclined plane, about 1m50 on each side.

The boy walks in front, Splingaerd and I follow.

We take measured steps downward, we go further down, and then even further. We often slip on the spongy ground that strains our steps.

At one point, my companion fell to the ground and in his fall, extinguished his lamp and mine.

The atmosphere is humid, hot and heavy, we perspire and go down further. Bent over, half, sometimes crawling, sometimes sliding, we find this little underground walk hardly recreational, especially after a course of 1 / 2 hour before we see anything.

Finally, we arrive at a construction site in front of the untapped vein approximately 20 cm thick. The woodwork is very limited, we also see many signs of collapse.

Our boy tells us that a little further we will see the workers working. The floor of the gallery is now very wet, and we see why. We meet workers carrying vessels filled with water, they carry these to the surface and they spill more or less along the length of their route.

I have to say that this exhausting system is quite primitive!

The air is becoming increasingly rarified, and we breathe with difficulty. We often have to stop to catch our breath, sweat dripping from our foreheads and we still move forward.

S. asks the boy if we are close to getting to the face of the excavation, he said no.

The gallery is shrinking so we walk doubled over, soaked and floundering in the mud. Tired of seeing nothing, S. asks our boy questions and he ended by saying that, further, we will walk along a gallery submerged under two feet of water where the air will be even more rarefied and warmer.

We talk it over and S. believes we should not to push our underground travels any further. He explains that we might suffocate, and be soaked up to our waists, and that not being able to change, we would have to wear these wet clothes all day.

I confess that my engineer’s eagerness, already dampened by the rarefied air and the water were wading through, ends up vanquished by S’s arguments.

…..

Back to our palanquins after leaving the mine, we continue our journey towards Kalgan, when we come to a fork in the road.

Which path should we take, the left or the right?

S. consults the drivers, Chang and finally the cook. They tell him go right, go left, so in short, we don’t know which path to follow.

S. told me to get back into my palanquin and to stay out of sight. I see him walking away in the direction of a Chinese man on a donkey who is heading towards us.

Soon my companion joins him and addresses him. The man gets down from his donkey and they talk at length. After about 5 minutes of talking, their conversation still do not appear likely to be ending soon. Ten minutes later, S. returned and ordered the carriers to take the left path, and we are once more on the road to Kalgan.

Intrigued by their long conversation, I get off from my palanquin and go to S.

Well, what took you so long to tell the citizen that we just met?

I asked for directions.

And for that, you talked for 10 minutes?

Certainly, you have to do that in China.

How so?

In China, it takes 10 minutes just to ask directions. If you’re on horse, donkey or camel, you have to get off your mount, according to Chinese courtesy. Only then can you address him, bidding him a good day, remark on how fine the weather is, ask him if he has had a good harvest, inquire about his health, adding that his children must be very good looking, judging by their father, and talk to him about his horses, his home, his village, clothing etc etc … After all that, you can ask him the most natural and most indifferent way if he would know which road leads to a certain place. Only then does one have a chance of getting the right directions.

…..

For our return to the inn, we are accompanied by a servant carrying a large paper lantern to guide our steps.

Towns in China are not lit at night; so to get an exact idea of Peking at night, just close yourself in a dark closet.

This nighttime walk is quite original; here and there you can see a lamp illuminating the inside of a store; or the fleeting light of a paper lantern going by, because one does not go out at night except with a lantern.

After going down streets and alleys, each darker than the other, we arrive at one of the city gates.

Since our inn is outside the walls, we need to have the gate opened for us.

(All the gates in Chinese cities open and close with the rising and setting of the sun.)

The corporal, with lantern in hand, does not seem willing to let us through.

Splingaerd engages him in a long conversation, and ends up slipping a string of coins into his hand. Then only does the gate open.

In the new world as in the old, gold is the universal door opener.

May 20[A?]**

The number of Customs posts administered by [Chinese] mandarins are fifty times fewer than those administered by the famous Mr. Hart and his European employees. European employees are well paid and honest. In eschewing its own people for the customs posts, the Chinese government has paid a resounding tribute to the honorable character of Europeans.

…..

While talking about these serious issues, my companion and I approach the town of Kalgan.

Kalgan is the Russian [Mongolian, actually] name, and Zhangjiakou is the Chinese name of this great city.

We quicken our pace because we are very pleased to arrive at Kalgan. My companion has a warehouse there run by a German Mr Groesel.

The house of these gentlemen is located outside the city walls and there I find a most cordial and friendly welcome.

As mentioned already, their trade consists of sending into Mongolia caravans of camels loaded with fabrics and English items purchased at Tianjin. They then trade these with the Mongols, mainly for camel hair. When the caravan has exchanged all its cargo, it heads back to Tianjin to sell all these bundles of camel hair and to pick up new goods to trade.

This style of trade is certainly primitive, but from the point of view of local color, it does not lack a certain charm!

Along the route, one can see continuous caravans of 10 to 100 camels. Some are heading for Tianjin, others returning to Mongolia.

…..

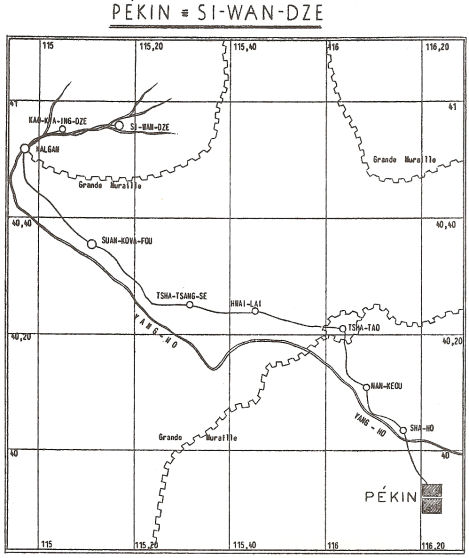

Map of path from Peking to Kalgan

Kalgan is a city located on the outer Great Wall of China, on the border with Mongolia, and is located on a tributary of the Wen-Ho.

The population is estimated at 200,000.

Its trade business is very important since all goods traded between Russia and China pass through Siberia, across Mongolia by entering Kalgan in the Empire of Flowers.

Almost every day in season, there are departures of caravans to Kiatcha, the first Russian city to be found on the border of Siberia. It is 1500km from Kalgan to Kiatcha, but imagine crossing the entire Gobi Desert!

This enormous distance is covered in 10 days by couriers of the Russian post, who work in relays, jumping from one horse to another, and galloping day and night. This man must be fairly worn out by the time he arrives at Kiatchka. …

Camel caravans take 30 days, and convoys of oxen-drawn carts take 3 months to cross these vast spaces.

…..

May 19(B?)

Today my excellent friend Mr. Splingaerd suggests I go to Bourgaltai, the first Mongolian city on the road to Siberia about 100 lis from Kalgan.

Each mounted on a mule, we leave early. The road enters the mountains the Chinese call Im-Chaun, and Mongols Ching-Ghan-Oula. In this country, the roads are often formed along the beds of streams that the season left to dry, they are only small and large rocks, gullies carved by the erosive force of water.

We must, however, tear ourselves from this beautiful spectacle as dusk comes and we must reach Bourgaltaî.

Here we find a small dirty inn, ugly and smelly. We must spend the night on a great kang in the company of twenty people, Chinese and Mongols. For my part, I lie between Splingaerd to my right and a fat lama on my left.

[putting up with] That night should certainly earn me a good hunting party!

Around 23:00, all these people start eating while talking loudly. I’m so used to being an object of great curiosity to the natives that I do not even notice them. Annoyed at not being able to sleep because of the chatter of my companions, I look forward to the end of their meal.

The scene is not devoid of local color, our room was quite large, lighted by three miserable little oil lamps. I cannot distinguish either corner or the ceiling of the room, I see only what lies in spaces lit with three lights form the center, Outside of this, the thickest darkness reigns.

Here is a Chinaman occupied with combing his long queue, what beautiful hair, his neighbor uses his fingers to eat long filaments that he fishes from a pot, I have learned since then that it was oatmeal flour noodles.

My big lama, is reciting out lout aloud a sort of rosary. A little further away is a lame man smoking a tobacco that stinks up the entire room, three sleepers at the end of kang snore together, and a large Mongolian devil is grooming his feet, which does not improve the perfumes that we breathe here.

…..

It is past midnight, the talking laughing and snoring continues. It is impossible for me to sleep.

Mongolia is beautiful, it has lots of cachet, but frankly at this moment, I prefer a little less cachet and a little more sleep …

Splingaerd who is accustomed to the sound of Chinese inns sleeps as if nothing was happening.

Finally, conversations cease, and everyone goes to bed, in another moment will be able to sleep. Strange how these people fall asleep quickly, as soon as they lie down, they sleep immediately. Well good, then the general snoring begins, what music, great God! Each in a different tone and the dog joins in …

May 20 [B]

…..

A fat boy leaves the group and speaks to Splingaerd. It seems that he invites us into his tent. My dear friend is truly amazing; here he is speaking with the Mongols with the same ease with which he speaks to the Chinese!

Off our mules, we entered through a very low wooden door into the abode of this brave man.

Yurt, Mongolian tent dwelling

The Mongolian tents are circular, shaped like umbrellas, they are 4 or 5 meters in diameter and 3 meters high at center. The framework is formed by an assembly of movable wooden frames that can expand and contract at will. The roof is supported by ribs like a large umbrella. This frame is reminiscent of our chicken coops. A large hole is formed at the center of the rooftop, through which the smoke escapes.

The door is two panels with a threshold formed by a thick wooden tie.

Long pieces of very thick camelhair felt cover the roof and sides of the tent, and the ground is covered with carpets.

In the middle, a fire of camel dung emits copious smoke that fills the entire space of the tent and makes the air almost suffocating.

The interior is divided into two parts, the right side is reserved for women and the men left. We enter through the left side.

These people give us a warm welcome and offered us tea and brandy made of fermented mare’s milk.

May 21

The next day we got back on the road to Kalgan, again through the mountains.

S. tells me everything our Mongols yesterday told him, and he gives me very curious details about the habits of these populations.

Marriages are made by matchmakers. The influence and authority of parents is absolutely the future spouses does not know each other, often they have never seen each other. The girl never brings a dowry, it is the young man who must send gifts to the family of his future wife. The gifts are arranged in advance to the minutest details. The marriage contract is a real sales contract. The Tartars say “we sold our daughter to this family … I bought So and So’s daughter for my son.

They haggle, they bargain, and when, the number of sheep, cattle, pounds of butter, pieces of cloth, etc. … is finally agreed upon, only then the contract is signed and the girl belongs the buyer.

May 22

The happy times I spent in Kalgan at the home of Mr. Splingaerd along with his partner Mr. Groesel, is a time that I will always remember with pleasure. These two gentlemen were so good, so kind to me, always willing help me with my excursions, putting at my disposal their horses, camels, mules and servants, and in a word, their whole household, that I am hereby expressing my gratitude to them.

Never shall I forget the excellent ties of friendship that developed between Mr. Splingaerd and me.

Wishing to spend the feast of the Ascension at the diocesan seat of the Belgian mission, my good friend S. again had the extreme kindness of accompanying me to Si-Wan Tse. It was by mule that we took this trip. Our luggage was placed in a cart and left in the care of Chang, my servant.

Leaving Kalgan by the door in the Great Wall, we were once again in Mongolia. We travel along a broad valley, often wading across the wide stream that meanders through it.

It’s always the same landscape, bare and barren gray shale mountains without vegetation, rocky streams and flat connected valleys.

Although we are in Mongolia, traveling along the mountain range that separates China from the Mongolian plateau, the country bears no resemblance to “The Land of Grass.”

Here’s an entirely Chinese village, the houses are made of earth, roofs and walls, and it also looks like a Lapp village.

In the evening we arrived at Kao-Yung Hsia … … .. and we head for the humble mission headed by Mr Otto.

Poor Mr. Otto is so pleased, so happy to receive a European in his home that he communicates his joy and happiness.

He received us in a truly princely manner, given the resources of his village. Remember that Kao-Yung Hsia has only 1,000 inhabitants and of these only 144 are Christians. The church is very simple, but clean and well kept, the rectory is small but well arranged.

To the great delight of the Christians assembled in the courtyard, I start singing La Brabançonne accompanied by Splingaerd and the applause of Mr. Otto.

May 23

Having spent several days in Xiwanzi and having meandered in different directions, I will summarize what I have learned about the Catholic missions in these countries.

To begin with Xiwanzi, I would say that this village of 1,800 inhabitants, with the exception of three families, is entirely Christian. It contains a beautiful church, a diocesan office, which while not luxurious, is quite adequate, a seminary and a branch of Holy Childhood under the direction of Chinese nuns.

…..

This morning Splingaerd suggests a visit with him to a silver mine located in Ghol-Chin. From Xiwanzi to the mine and back, is a trek of 12 leagues. Here, this seems like a stroll.

We leave on mission horses. They are good little Mongolian ponies that ride like the wind.

I see for the first time on this trip, the huge crows that here in Mongolia, perform the role of gravediggers.

Around noon, doubting the path we must follow, my companion stops at a farm to ask directions. There, dismounted, he talks for a long time with an old Chinese man while I ride around the farm yard.

Finally, S. gets back on his pony and said in a rather annoyed tone:

“You are the reason that this man would certainly have given false information”

“Why? “I replied

“Because you have seriously offended him by entering his home without getting off your horse. The Chinese say that only people who have lost face (that is to say the honor), in a word, the robbers, who behave this way. They stay on their horses in case they fall into a trap, and need to make a quick getaway. ”

After many pauses, steps and missteps, we find the mine. It is now completely abandoned and no longer offers anything of interest.

We have a bite at Pai-Quai-Cou, a small Chinese Christianity with a miserable church. We find a Chinese Catholic priest who bends over backwards to entertain us well.

In the evening we were back at Xiwanzi. All day there was a furious wind and cold, we can see it comes from Siberia.

…

Last night I heard the mission watchman pass by my room. These watchmen have a strange habit: they walk around with a lantern and tap a small mallet on a wooden board. The noise made is to warn thieves of their arrival. In this way the thieves have time to hide and are not obliged to cause trouble for the brave watchman. It is not very practical, but then I wonder what purpose do the night watchmen serve?

……

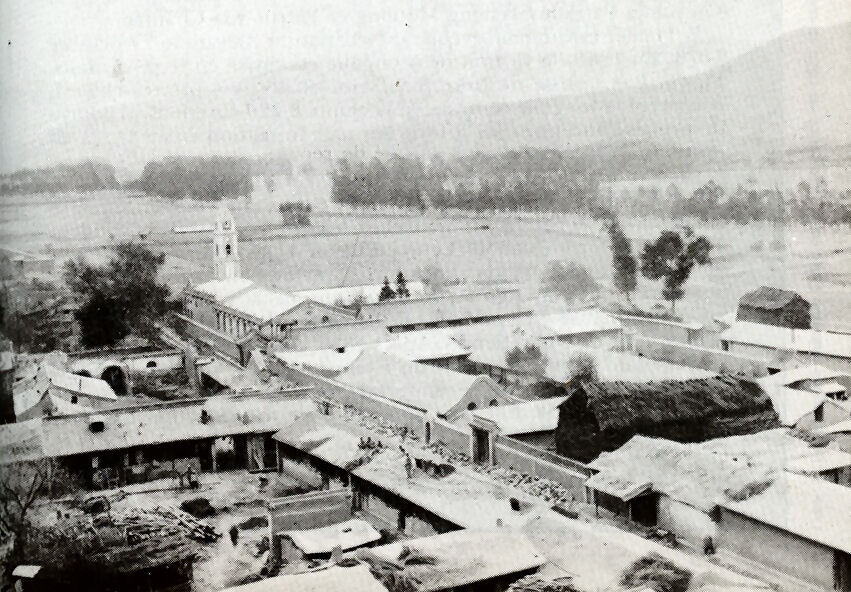

Xiwanze

May 23

As Splingaerd returns to Kalgan today, and I don’t want my amiable traveling companion to go alone I also left Xiwanzi.

——–

After these happy days spent in the excellent company of all these good missionaries, I am obliged to bid them adieu, carrying with me always the memory of Monseigneur Bax’ warm reception.

June 8

This evening Mr. Splingaerd Kalgan left to rejoin his family who lives in Huhehote, Guihuacheng in Chinese, a very important city located in Mongolia, near the Huang He or Yellow River.

Given the limited opportunities I have, without special permission from the Chinese government, to visit coal mines located near the Huang He, I decide not to accompany my amiable companion any further. This simple trip require 25 to 30 days and would require 1,000 to 1,200 miles on horseback, by camel and on foot.

Mr. Splingaerd leaves us, bearing all my thanks and also my regret that we to have to separate.

As for me, I’m starting my preparations for tomorrow, this time I am reduced to my own resources, a lone European accompanied by my servant Chang and three mule drivers. I must return to Beijing from Kalgan, a distance of about 200 km, which will require 5 days of travel.

…..

If these short travel notes have interested my readers, I ask you to forget the form and to remember only the content

Mons [Belgium], January 13, 1882