Assembling the Paul Puzzle

The Belgian Mandarin Books

Assembling the Paul Puzzle

The Life of Paul Splingaerd

(Brussels,1842 – Xian,1906)

by Anne Splingaerd Megowan

Since the publication of The Belgian Mandarin in 2008 much has turned up of interest to those who want to learn more about “the mysterious Lin Darin.” Assembling the Paul Puzzle includes new pictures, articles and events that relate to Paul Splingaerd, told in a personal, “intimist” style by his great granddaughter, Anne Splingaerd.

Ebook:

Order your copy today!

What’s the Book About

Researching the life of the foundling who came to be known as “The Belgian Mandarin” turned out to be an E ticket ride that did not end with the publication of my 2008 book, The Belgian Mandarin*. A vast amount of information about Paul Splingaerd has turned up since then, and in combination with the events and coincidences encountered in writing the earlier book, a host of material begged to be presented in follow-up book, so I put it together in Assembling the Paul Puzzle.

This companion to The Belgian Mandarin provides a “behind-the-scenes” account of my pursuit of information on my fascinating great grandfather, and incorporates many photos and documents that have surfaced since 2008. If you are a known relative, or played any part in contributing to Paul’s story, you are probably in it.

Initially distributed on flash drives to interested relatives, digital or print copies will be available by writing me, anne@splingaerd.net.

I hope you will enjoy this continuation of Paul’s story.

Anne Splingaerd Megowan

January, 2016

Camarillo, California

Where to Buy

Assembling the Paul Puzzle is available right here at: Splingaerd.net.

Assembling the Paul Puzzle

Table of Contents

| Introduction | 1 | |

| Chapter 1 | The First Pieces | 3 |

| Chapter 2 | A Portal Appears | 8 |

| Chapter 3 | First Successes | 13 |

| Chapter 4 | Back to the land of my birth | 30 |

| Chapter 5 | On to Mongolia | 48 |

| Chapter 6 | Lanzhou, an Important Part of the Puzzle | 61 |

| Chapter 7 | Bringing Paul Back to Jiuquan | 80 |

| Chapter 8 | “Back in Xian, where Paul Died | 104 |

| Chapter 9 | Yangtse (Yangzi) River and Shanghai | 110 |

| Chapter 10 | In Paul’s homeland | 116 |

| Chapter 11 | Heirlooms Emerge in South America | 133 |

| Chapter 12 | Following up in the US | 145 |

| Chapter 13 | Finding Paul in Other Publications | 157 |

| Chapter 14 | Interesting connections along the way | 191 |

| Chapter 15 | The Bridge between LA and LANZHOU | 215 |

| Chapter 16 | Paul’s last journey | 234 |

| Chapter 17 | Posing with Paul | 246 |

| Chapter 18 | Family Mysteries – puzzles that may never get resolved | 254 |

| Chapter 19 | The End of the Line | 267 |

| Chapter 20 | Conclusion | 269 |

Introduction

Researching the life of the foundling who came to be known as “The Belgian Mandarin” turned out to be an E ticket ride that did not end with the publication of my2008 book, The Belgian Mandarin*. A vast amount of information about Paul Splingaerd has turned up since then, and in combination with the events and coincidences encountered in writing the earlier book, a host of material begged to be presented in follow-up book, so I put it together in Assembling the Paul Puzzle .

This companion to The Belgian Mandarin provides a “behind-the-scenes” account of my pursuit of information on my fascinating great grandfather, and incorporates many photos and documents that have surfaced since 2008. If you are a known relative, or played any part in contributing to Paul’s story, you are probably in it.

Initially distributed on flash drives to interested relatives, digital or print copies will be available by writing me, anne@splingaerd.net. I hope you will enjoy this continuation of Paul’s story.

Anne Splingaerd Megowan

January, 2016

Camarillo, California

* Paul’s biography, The Belgian Mandarin is available from the publisher,

Chapter 1 – The First Pieces

Among the items Mum and Dad brought with them when we left China in 1947 were two oil portraits. Because our family was limited in what we could carry out of China, the fact that these portraits came with us meant they were important. The impression was reinforced when I observed the reverence with which they handled the two unframed oil paintings on canvas, protected by cardboard, and wrapped in linens. It was not until our family was settled in Mexico City in 1958 that Mum had the paintings framed in gold-foiled frames.

Figure 1. Oil portraits of Paul Splingaerd and his wife at our home in Mexico City.

Figure 2. The portraits are now at the Phoenix, Arizona home of Paul’s great grandson, Peter Splingaerd,shown here with his wife Alice Wright. Peter is the last male heir of the Splingaerd name.

One portrait was of a red-bearded Caucasian man wearing a formal-looking dark Chinese robe with a long necklace, and the other portrait was of a Chinese woman, similarly dressed, also wearing a long necklace. They were Dad’s grandparents, the Belgian, Paul Splingaerd, who became a mandarin in the imperial court of China, and his Chinese wife. Mum and Dad did not know why Paul was made a mandarin, nor the name of his Chinese wife. The bits of information that were passed down to me by relatives were that he was a

The bits of information that were passed down to me by relatives were that he was a mandarin in the court of China. The family members I asked said they assumed he had become a mandarin by marrying into Chinese royalty. This turned out to be an erroneous assumption, as I found out Paul earned mandarin status on his own merit.

To be fair, the shroud of ignorance surrounding Paul’s life, if indeed deliberate, was influenced by the time and place in which my parents grew up. In China and elsewhere, one has to maintain ‘face’ to survive in society. The desirable face was naturally to be that of a high born, wealthy, cultured and educated individual. This would have been a difficult façade to maintain if people knew that your ancestor had none of the above, so it was kept quiet. Paul’s humble origins and any facts that might have detracted from the image of gentility may have honestly been forgotten through the years, or been victim of voluntary amnesia.

As an American not burdened by the practice of establishing worthiness based on title or lineage, I am quite proud of Paul’s ability to rise from basically nothing to prominence on the merit of his own God-given wit and will. In his native European homeland, Paul’s lack of inherited title and his limited education would have stifled his chances for advancement. Although Paul was made a ‘Chevalier de L’Ordre de la Couronne’ by King Leopold II, it was in China that he accomplished more.

Had I learned to read and write Chinese as a youngster, it would have been easier for me as an adult to research Paul’s life in China. Mum and Dad could speak Chinese as they were both born and raised in North China, and had Chinese mothers, but neither had studied the language formally enough to be able to read and write the language well. Dad’s father, Remy, had hired a former court eunuch, to teach his children his own maternal language, but this instruction ended when Remy died when Dad was eleven, and was sent away to a French boarding school. In those colonial times, in stark contrast to today, it was deemed more important to be educated in the European curriculum than to learn to read and write the native language. I tried to make up for my own lack of mastery of the Chinese language by taking Chinese lessons once I embarked on the pursuit of Paul. Even though my pre-teen years were spent in the Orient, I never really mastered written Chinese, and only picked up verbal Chinese as a child to communicate with my Chinese grandmothers, Laolao and Nainai and my Lao Amah. When I lived in Hong Kong and Japan, I was able to talk to neighborhood friends in basic Cantonese and Japanese, but did not have formal lessons in the written language that brought me beyond the beginning “a i u e o, ka ki ku ke ko…” of hiragana, which I forgot after I left Japan and my exposure to the language.

Although Dad’s mother was Chinese, he was educated in English and French because that was what was taught at Tientsin’s St. Louis College, the school attended by most of the Catholic boys in Tianjin. It was the school my uncles, cousins and brother attended as well. My father, Joseph Splingaerd, was a Belgian citizen because according to the law of the time, if your father was Belgian, you were Belgian, too, regardless of where you were born. Mum had British citizenship for the same reason*. Laws have changed since then, but by that now-obsolete law, my brother and I were also born with Belgian citizenship

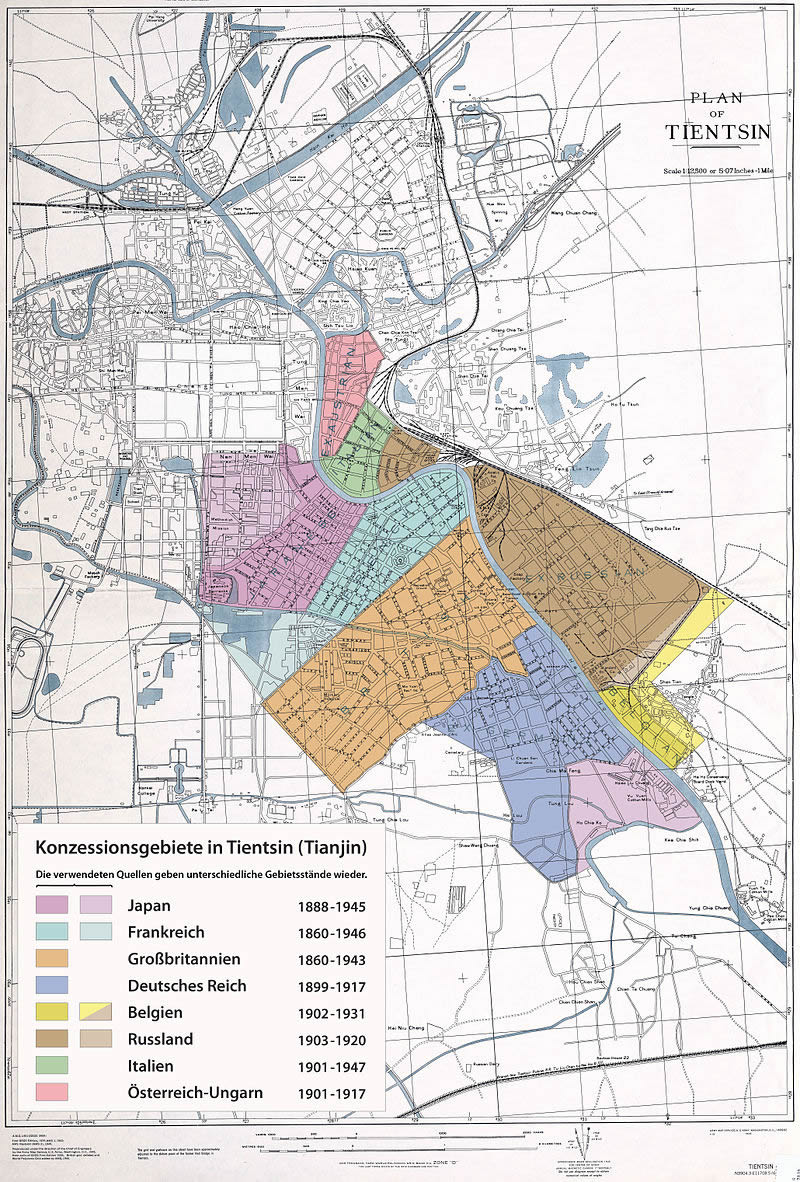

Dad lived in the French Concession, and Mum in the British, and probably met becausethey both attended Catholic schools, and their siblings knew each other. The Belgians had a short-lived (1902-1931) and small concession than for providing a trolley and lighting to the concessions **, where a number of Splingaerd men, Dad included were employed. More on the tramways: http://www.goens-pourbaix.be/multima-pourbaix/Mandarijn/Tram/tram.htm.

To return to the portraits, all I learned from my folks about the red-bearded mandarin was that his name was Paul Splingaerd, and that he went to China as a “lay missionary” with the Scheut missionaries, and became an important mandarin. I also was told that he was decorated by his Belgian king. I remember my brother Peter and I played with the medal as kids. Dad had the medal because was the only acknowledged direct male descendant who produced a son. I don’t remember ever being told the name of the decoration, or why it was awarded to Paul; what I remember was that it was attached to a deep red moiré ribbon with two prongs for attaching it, and the medal itself was a design of five white enamel rays, interspersed with smaller gold ones, radiating from a blue enamel circle with a gold crown in the middle. The family was very proud of this medal, and the fact that it was given to Paul by his king. The last time I saw the actual medal was at my brother’s home in San Francisco, it had lost most of its enamel, and the ribbon

To return to the portraits, all I learned from my folks about the red-bearded mandarin was that his name was Paul Splingaerd, and that he went to China as a “lay missionary” with the Scheut missionaries, and became an important mandarin. I also was told that he was decorated by his Belgian king. I remember my brother Peter and I played with the medal as kids. Dad had the medal because was the only acknowledged direct male descendant who produced a son. I don’t remember ever being told the name of the decoration, or why it was awarded to Paul; what I remember was that it was attached to a deep red moiré ribbon with two prongs for attaching it, and the medal itself was a design of five white enamel rays, interspersed with smaller gold ones, radiating from a blue enamel circle with a gold crown in the middle. The family was very proud of this medal, and the fact that it was given to Paul by his king. The last time I saw the actual medal was at my brother’s home in San Francisco, it had lost most of its enamel, and the ribbon

was virtually worn away, just as King Leopold’s reputation has been in recent years.

Figure 3 This map of Tientsin foreign concessions downloaded from Wikipedia shows the yellow “L”-shaped Belgian Concession at the right.

Of the twelve children of Paul and Catherine who survived to adulthood, three were boys, and the four older daughters became nuns. The three sons, Alphonse, Remy and Jean-Baptiste, remained in China and married Chinese women. The younger girls married Belgians who had gone to work in China, and went with their husbands when they returned to Europe.

Of the twelve children of Paul and Catherine who survived to adulthood, three were boys, and the four older daughters became nuns. The three sons, Alphonse, Remy and Jean-Baptiste, remained in China and married Chinese women. The younger girls married Belgians who had gone to work in China, and went with their husbands when they returned to Europe.

I knew that my dad and my brother were the last male heirs to the Splingaerd name, and this was pretty much what I knew of Dad’s family for most of my life, till 1994.if

If you’d like to download a copy of this except , click on the link below:

*Mary (Mum) Anderson’s father, Alexander Anderson, had traveled from Scotland to China at the beginning of the 20th to workwith a fellow Glaswegian who had started a school for the blind, “The Hill Murray Mission to the Blind and illiterate sighted inNorth China.”

** In 1904, China and Belgium signed a contract with Compagnie de Tramways et d’Éclairage de Tientsin, which stated that “this company has the exclusive right to produce and maintain the electric light and trolley systems for a term of 50 years.” In 1906, with the opening of the first route of the trolley system, Tianjin became the first city in China with a modern public transportation system (Shanghai had to wait till 1908 to get electric tramways). The supply of electricity and lighting and the trolley business were profitable ventures. All the rolling stock was supplied by Belgian industries, with a small exception: the original electrical equipment came from Germany. By 1914, the network was covering the Chinese city and the Austrian, French, Italian, Japanese and Russian concessions. (http://en.wikipedia.org /wiki/Concessions_in_Tianjin)

Media Coverage

| 31Aug09 | Anne’s Report on 2009 Lanzhou Visit for Centenial Celebration of First Iron Bridge Across the Yellow River on August 26 |  |

| 27Aug09 | The Lanzhou Bridge Centennial Celebration on August 26, 2009 generated a great deal of coverage in the Chinese press. Pictures of the Ceremonies, the visiting descendents of Paul Splingaerd, and historical photos are included. There are a couple of stories going beyond the formal press releases and featuring interviews with people having recollections of the history of the bridge since its construction.

http://www.qj023.com/bbs/thread-8811-1-1.html http://www.tc.cn/news/newsshow-90135.html http://www.sxworker.com/xinwen/gn/2009-08-27/840.html http://www.zgts.gov.cn/xwzx/gnxw/2009/08/27092055829.html http://books.sina.com.tw/article/20090827/2080771.html http://xw.chinawestnews.net/system/2009/08/27/010173789.shtml http://www.gscn.com.cn/pub/gansu/shms/2009/08/21/1250825577683.html http://bbs.club.sina.com.cn/thread-346/table-27722-7718.html Similar article to above. http://www.gscn.com.cn/pub/cul/whtt/2009/08/27/1251339509292.html This article relates the history of the Splingaerd family intertwinement with the Lanzhou Bridge development. It contains different pictures from the standard press release and includes a few historical photos. Anne is mentioned. http://lz.gansudaily.com.cn/system/2009/08/21/011235313.shtml |

|

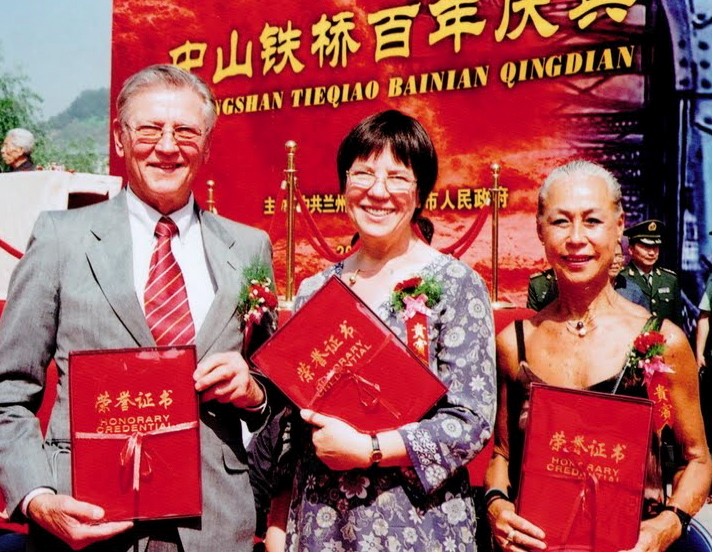

| 27Aug09 | The Lanzhou Bridge Centennial Celebration in August 2009 developed a great deal of media attention in China. Anne’s aunt, Zhang Jian Qin, holding Anne’s book, The Belgian Mandarin, was featured in an hour-long documentary about the involvement of Paul Splingaerd and his associates in the introduction of European business and engineering to Lanzhou region. This picture was also featured in a Lanzhou newspaper article in August 2009 about Paul’s descendants becoming honorary citizens of the city. |  |

| 26Apr09 | Los Angeles Times Festival of Books – 2009 Press Release for 2009 Festival of Book   |

|

| 8Nov08 | Huldenberg article on Splingaerd Reunion (Flemish) |  |

| 12May08 | May 2008 Interview by Los Angeles China Daily Newspaper (Chinese) | |

| Apr08 | April 2008 Interview by Santa Monica Star | |

| Nov2006 | Interview by Not Born Yesterday |  |

| 13Oct05 | Review of 2005 Trip by Chinese Press |